"That's how we've always done it!" may actually be a much better rallying cry than we might be willing to credit. Let us use that paradigm to lend some context to ensuring that the right food safety behaviors and practices are properly transferred from "those who know" to "those who need to know" (whether they know they need it or not). Understanding how and why something is "done that way" goes a long way toward driving positive change while simultaneously minimizing risk to public health.

This article will provide many proven lessons in this regard, particularly for when a long-tenured subject matter expert (SME) leaves an organization. How is that person replaced? The suggestions and tenets shared in this article are founded on proven scientific principles and actions, and on instincts honed by long-term experiences in the food business. We share best practices, not just opinion, to increase the organization's effectiveness at planning for and executing a transfer of experience and skills from one generation to another.

The Need for Skills Transfer

All companies run across the need to replace their revered SMEs. When the person who knows "everything" and has been around "forever" decides to retire or leaves the business, companies must find a way to replace this lost knowledge. Odds are that this expert holds significant "legacy knowledge" inherent to a long-tenured career, and the expert has learned it, and can apply it, at all levels of the organization. The SME is typically equally comfortable on the production floor as in the executive suite, and on any work shift. The SME is involved in many integral touchpoints, and legacy knowledge transfer occurs almost seamlessly.

Generational changes, as part of normal turnover in a company, can also catalyze the same need for knowledge transfer. This seems particularly germane these days with such a large percentage of "boomers" leaving the workforce, along with the effect the COVID-19 pandemic has had on workers.

Take the example of the "spice room person," the revered SME of their space. They are usually highly tenured and experienced, and run their domain (the spice blending room) with the proverbial iron fist. All batches are correct, all of the time, and all audits are passed. However, when this person is on vacation, all kinds of problems occur. Is that their fault? Is it due to a lack of training? Is it due to a lack of accountability on the part of their management? Or are the underlying food safety processes and food safety culture not supportive of this kind of "generational" transfer?

What are the benefits the "spice room person" has been bringing, and therefore need to be replicated, captured, and engrained in the organizational fabric? These may relate to preventive controls, risk analysis, and problem solving, all essential for the handling of "special causes" (i.e., mistakes), as well as "common causes" (addressed by strong, established processes).

In many companies, the revered SME patrols the frontline and the production floor at will, and with ease. Since this SME is likely in regular communication with senior management, this means that the SME is a great communication conduit between the senior leaders and the frontline workers. As two-way communication with the frontline is often one of the weakest links in driving change management, this is a "gap" that will need attention once the SME leaves.

Also, the SME is likely the "keeper of the why." The SME has been around long enough to have a thorough knowledge of how and why processes and practices have been changed over time. When the SME leaves, the organization needs a gatekeeping system to ensure that existing systems and processes are not changed without an understanding of the underlying reasons why they exist in their current forms. The underlying conditions and inherent assumptions may indeed have changed, but these need to be recognized and understood before straying too far from "we always do it that way." Gatekeepers can be, for example, mid-level managers who approve process changes before they are implemented—and who make changes only with a complete understand of the "why."

Why is "why" so important? Legacy solutions are real. If they are discarded or given too little attention, then the organization is likely not to notice for quite some time—and at that point, it may be too late to prevent a costly recall or product loss. That insidious result can be unrecoverable. It is always worth remembering that changes to systems and cultures are journeys, not single events. For example, when the food industry develops a best practice process (e.g., publishing sanitary equipment design principles), it usually takes years of work across many organizations and involves trial and error. Literature1 provides examples of why we end up with specific best practices. These steps must be understood.

Traditional Ways of Capturing and Transferring Organizational Memory and Knowledge

Several proven, common techniques exist for transferring knowledge in the organization, particularly as a revered SME is exiting. We are sharing these approaches to provide a contrast later in this article with other, better methods:

Write It Down

- Report files, corrective and preventive action (CAPA) files, third-party audit reports, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and sanitation SOPs—all are incident and data captures that can be useful for comparison in the face of a problem

- Established protocols, work instructions, ways to execute tasks on the manufacturing floor (as opposed to relying on someone who "should know")—all can help ensure proper practices, even in the face of a problem

- Formal reports, scientific reviews, after-action reports, process-based manufacturing operating procedures—these might include the historical basis and the "why" (but typically do not), and can serve as effective pattern captures for application to new problems.

Shadow the SME

- Meet and connect with the SME's network outside of the company

- Ask the SME to give webinars and seminars

- Take gemba walks with the SME around the plant

- Invite the SME to share stories (e.g., over Friday lunches or seminars on key subjects).

Hang on to the SME as Long as Possible

- The organization should expect (and hold accountable) the SME to continue to communicate with the frontline, and the organization should recognize and reward this

- One of the downsides to hanging on is that it avoids the inevitable, and reinforces the belief that the SME is the source of all solutions to food safety issues (which likely reinforces that "senior management" is the source of all solutions also).

These approaches can be somewhat beneficial, but reading through reports and listening to long-winded stories may not be the most appealing methods of knowledge transfer for some people. Also, ego has a tendency to get in the way of successful knowledge transfer. Many people believe they can do better, or would rather not be "biased" by the past, or do not take the time to reflect. A paradigm shift in thinking is needed. The truth is that losing a revered SME is a burden for an organization, and a company must be ready for this inevitable scenario.

The Fundamentals of Risk Assessment and Problem Solving

The essence of generational transfer (e.g., losing a revered SME) is actually all about risk management. Food safety risks to an organization continue to evolve as new ones arise. The organization must be capable of identifying and managing these risks. The culture of the organization must be conducive to problem solving.

What are key characteristics of good problem solving? In general, the best solution is likely not solving the problem at the level of the problem itself. Problems also differ in their makeup—some are logic-based, some are algorithm-based, some involve troubleshooting, and some involve design.2 Effective use of root-cause determination within the organization can catalyze transformational and trans-generational information flow and help solve problems.

Keep in mind that technology (e.g., whole genome sequencing) is a driver of change and, hence, new problems. New technology does not change the underlying food safety need for public health protection, however.

Recognize that the SME is likely extremely adept at identifying food safety risks to the business. These include current and real risks, as well as new and emerging risks. Risk identification and management are business-critical functions. When a revered SME leaves, it should be a reminder of the need to abandon the view that decisions should be made by a single authority (e.g., the SME or even the CEO). Rather, the sources of solutions must include broader teams.

Tools for a Paradigm Shift

We began this article with the admonition that the claim, "That's how we've always done it!" may deserve more credit. Consider Sisyphus, the Greek king forever forced to push a rock uphill, only to have it roll back down again. Suppose that this rock represents the legacy knowledge of a revered SME. Might the fact that it is difficult to get rid of that collective food safety knowledge be a good thing?

The company evolves, as does the "why we do what we do." Establishing why doing things "the way we always have" helps set fundamental principles; it does not need to be a reason for change. A transparent understanding of why and how we got here is crucial to examine why some long-ingrained practices should remain in effect.

Technicians and Supervisors

Often underestimated in their impact on knowledge and generational transfer are the floor-level employees and middle managers. They are the ones who can (and are expected to) execute a strong CAPA program, and they affect cost of poor quality (COPQ). Empowering this frontline is critical. All levels must have the same sense of pride, ownership, and responsibility to address matters that are out of process control. Seemingly small practices, such as daily huddles for enhancing communication and ongoing education to increase skills and knowledge, can go a long way.

The Value of Data

Risk assessment and problem-solving absolutely should be predicated on data. There is a need to be data-driven, with the right sense of urgency, the ability to obtain and acquire data, and the ability to assess and communicate learnings from this data. The CAPA process and COPQ data help define patterns and identify root causes. Process improvement and process control are critical. "Data can drive… a predictive state where actions are taken in advance of… a high-risk situation."1

Best Practice Technology to Capture Information and Learning

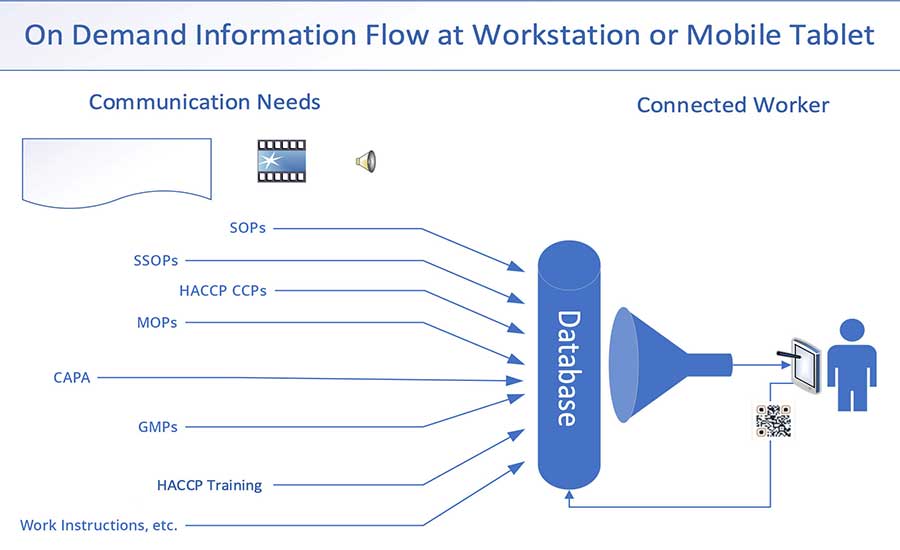

Thanks to improvements in electronic data collection, machine learning, and overall software capabilities, best practices for food safety operations now include using connected worker platforms. These platforms enable information to be literally at the fingertips of the on-the-floor team member. Think of the many points that individuals can access information by way of a tablet, phone, scanner, etc. The connected worker merely needs a tablet device to access processes or, better yet, to scan a QR code that will provide all of the required information (Figure 1).

The "connected worker" has ease of system access for immediate availability of information to the team; this also has huge benefits in limiting the need for off-floor time in training. Look at this as a means of preserving "why" and as the creation of a centralized digital library that includes work instructions, videos, and troubleshooting solutions, all easily viewed on the floor using tablets.

The integration of data from disparate sources is the critical step in creating a "connected worker." It is about integration of systems, not just having a bunch of systems. If you have a multi-plant operation, standardization of tasks is key. Digitized systems, maintained as current and available to on-the-floor team members, ensure consistency of tasks with the ability to register a team member's access to content and register on-premise training, encouraging efficient and effective processes.

Training (or is it Education)

Measuring the effectiveness of training is necessary to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the training programs. This drives continuous improvement. It is much more than simply having "GMP training" or "HACCP training" as once-per-year checkbox exercises. One must educate, not just train. Training may be useful for learning a specific task; education is useful for learning how to think. To quote David Jonassen, "Research has shown that knowledge constructed in the context of solving problems is better comprehended, retained, and therefore, more transferable."2

Learning How to Think and How to Solve Problems

As mentioned previously, a key skill for effective generational transfer is risk identification. Its cousin is problem solving. A simple tool in this regard to drive a focus on "why" (and therefore, root cause) is the use of the "Five Whys." Using this approach in the daily operating reports from supervisors and key operators can help educate everyone on getting to the real root cause and engage functions across the company to create solutions. Getting to the real root cause, not just checking a box and/or finding an immediate (but unsustainable) solution, is what counts.

Being able to assess risks and solve problems also relates to training, which in and of itself is fleeting and transitory. As just noted, education is what matters. Capturing knowledge is useless unless "effective, robust, and continually improved training programs"3 are established. As an example, a preventive maintenance program needs to be more than just keeping equipment running (i.e., training); it must also prevent food safety hazards and risks (i.e., education).4

Food Safety Culture

It is also critical to have the structure, practices, and motivation to build the right food safety culture, independent (yet inclusive of) revered SMEs. Having the right food safety culture creates engagement with team members. It involves reporting relationships, especially to define tasks and expectations, and holding the right people accountable. It includes identifying best practices and bringing them in from outside the organization when necessary, as well as the value of wide and diverse engagement and proactive and continual improvement. The best system can be undercut if the underlying culture is poor. Culture eats strategy for breakfast!

Teamwork

Teamwork is the deployment vehicle for the transformation of culture.5 Teams can go beyond a given individual's knowledge or ability. They can and should be used to address CAPA issues, along with significant COPQ problems. Having a team accountable as a collective unit is a powerful driver of understanding "why," and therefore, driving appropriate change.

The Generational Transfer

If handled properly, generational transfer is not a single event, nor even an event itself. "That's how we've always done it!" can become a very effective rallying cry—for not changing without identifying "how we got here." Hence, migrating from current practices can be accomplished with eyes wide open, knowing there is risk. Checking egos at the door facilitates this process.

Note that the above tools and principles will never truly take the place of a revered SME. If an organization has another SME, then that person should be provided with support and resources. The above tools and principles will also never replace the "human element"—i.e., a SME personally connecting with other employees. This is both valuable and honorable.

Generations will continue to move out, and in, within the workforce and the workplace. How can this inevitable process be made most effective? If you do not have a systems-based approach to adjusting to a new generation coming in as revered SMEs leave, then you are at risk of COPQ costs, higher turnover, and higher waste. These issues may not be noticed for some time, making recovery more difficult. This is why it is beneficial to make the right investments sooner rather than later.

What can an organization do to succeed? Keeping the standard data-capture and report-writing in place and working with the SME to tap as much knowledge as possible is a start. Then, get independent of all of that. Best practices now involve becoming data-based, identifying and managing risk, and having the organizational skills to solve problems with a team-based approach. Help keep the legacy knowledge rock from being pushed over the cliff.

References

- Butts, John. "The Journey to a State of Control." Food Safety Magazine, February/March 2011. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/3845-the-journey-to-a-state-of-control.

- Jonassen, David H. Learning to Solve Problems. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, May 2004.

- Wallace, C., N. Bogart, M. Bartikoski, and J. Butts. "Food Safety = Culture Science + Social Science + Food Science." Food Safety Magazine, April/May 2019. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/6626-food-safety-culture-science-social-science-food-science.

- Lijana, Bob. "Preventive Maintenance: Another Preventive Control?" Food Safety Magazine, August 17, 2021. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/7304-preventive-maintenance-another-preventive-control.

- Butts, John. "A Team Approach for Management of the Elements of a Listeria Intervention and Control Program." Agriculture, Food and Analytical Bacteriology 2, no. 1 (2010).

John Butts, Ph.D., is the Principal at Food Safety By Design LLC and the Advisor to the CEO at Land O' Frost Inc., where he was in the primary technical role for 47 years, having retired in 2021. As part of his succession plan, Dr. Butts founded Food Safety By Design LLC in 2010. Food Safety By Design helps producers of high-risk products learn how to prevent and manage food safety risks. Dr. Butts' specialty is the incorporation of food safety practices into company culture, including root cause identification using the "Seek and Destroy" scientific strategy for identifying and eliminating harborage sites for pathogens, which Dr. Butts developed earlier in his career. He is also a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine.

Gina Flores, M.B.A., is Vice President of Food Safety at Ruiz Foods. She is an accomplished food safety and quality professional with over 24 years of food industry experience in dual-jurisdiction regulated operations. She interacts at multiple levels to achieve company results by understanding the value of human capital and the dynamics to drive change in an organization. She also oversees programs that have led to improved food safety standards and certifications. She holds an M.B.A. degree and a B.S. degree in food science from California State University at Fresno.

Bob Lijana, M.Sc., has held director- and VP-level positions in food safety, quality, and operations for over 35 years at companies producing ready-to-eat foods, prepared meals, and pasteurized juices. He holds B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California–Berkeley, respectively.