Video credit: uuoott/Creatas Video via Getty Images

Where Food Safety Systems and Culture Collide: Do You Know Your Company's Psychosocial Risks?

Psychosocial risks become important to food safety when they have the potential for causing psychological or physical harm, and when they lead to deficiencies in expected food safety behaviors

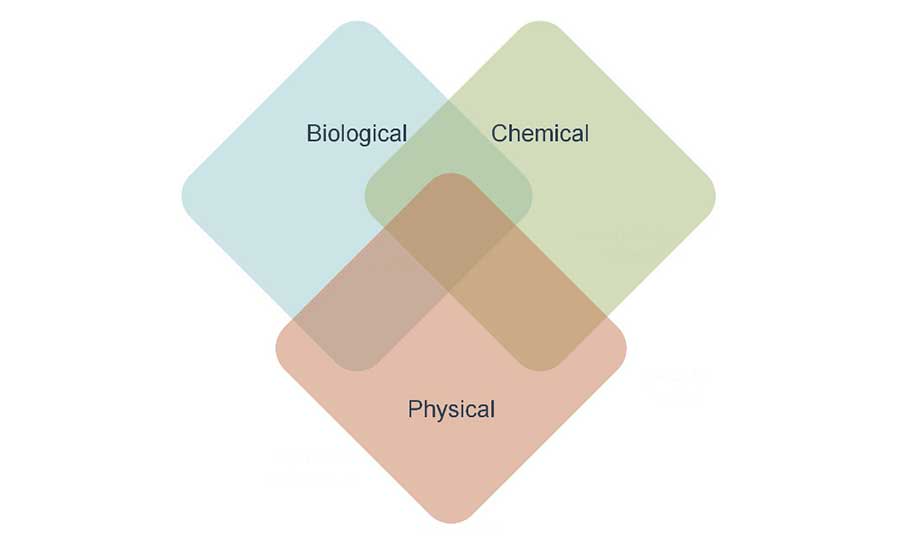

Is it possible that your well-thought-out hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) program is missing 25 percent of the food safety hazards in your plant? What if an assessment of the biological, chemical, and physical hazards (Figure 1) is simply not enough—that, at best, it is creating a compliance culture and false sense of security?

We believe that an assessment of your company's "psychosocial" risks can create the change that many food companies need.

Companies around the world have gotten quite adept at improving their food safety culture (and their overall corporate culture) on an ongoing basis to also improve their food safety systems. From other disciplines, we know there is a significant correlation between culture and risk taking.1 We believe this can be transferred to culture in food companies and their attendant food safety risks. As such, food safety risks have decreased with this impact of food safety culture, which is a marvelous accomplishment.

The foundation of any food safety system is the company's HACCP program, where biological, chemical, and physical hazards are assessed by a team that often comprises managers from different functional areas. The reason for involving managers from different areas is so that the company's product and process food safety risks can be appropriately identified, assessed, and managed. Prevailing wisdom from Codex, regulators, and third-party food safety standards is that this keeps consumers safe and the company out of trouble. The executive team can then turn its attention elsewhere, confident that the Food Safety and Quality Assurance (FSQA) team has everything in hand.

As is often the case, the company does well on food safety inspections and audits, further reinforcing the prevailing wisdom. All is well—until it isn't. Examples include Old Europe Cheese Inc., which is SQF-certified "at the highest level" but had a Listeria outbreak in 2022; J.M. Smucker, which is GFSI-certified but experienced a Salmonella outbreak in 2022; and Gills Onions, which is SQF-certified but had a Salmonella outbreak in 2023.

When disaster strikes, it often means that the executive team turns to question the performance of the FSQA team, or that the Food Safety team (the HACCP team) re-examines its hazard analysis to see what might have been missed. These actions usually do not give the answers to why a recall occurred, or why a consumer became ill. Why not? Because the actions to find solutions are limited to the same level at which the problem exists—systems, standards, and "proven" approaches are re-applied. The executive team, the FSQA team, and the HACCP team have been operating in a compliance culture, not an internalized culture where system and culture impacts on food safety are integrated.

This could mean that significant food safety hazards have been overlooked. Ironically, this is through the consequences of the risks associated with the very culture that executive teams are responsible for, expressed through the company's psychosocial hazards and risks.

Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Food Safety

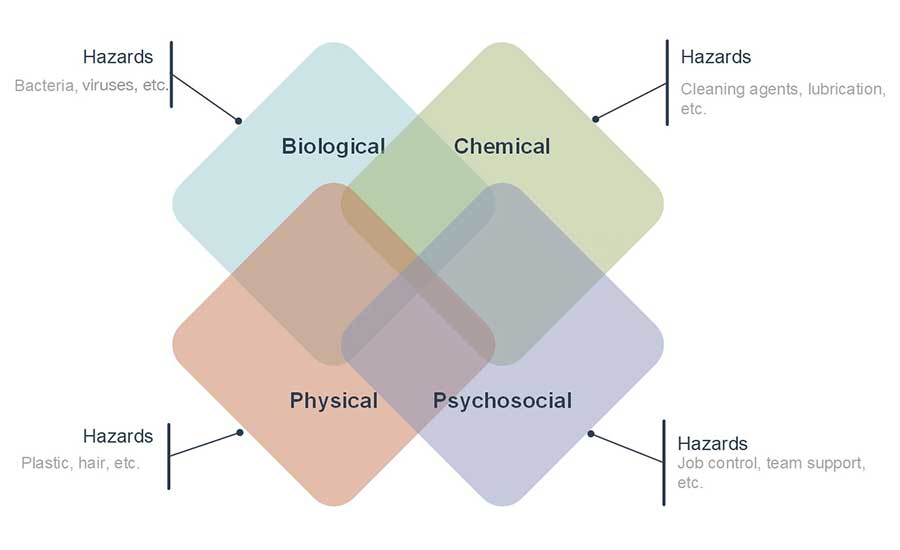

Psychosocial hazards, as defined by the International Labour Organization,2 can be seen as "the interactions of job content, work organization, and management, and other environmental and organizational conditions… and the employees' competencies and needs." These hazards can—as with the classic biological, chemical, and physical hazards—be turned into risks by assessing the likelihood and severity of the hazards (Figure 2).

Work-related psychosocial risks can also be defined as "those risks associated with the way work is organized, designed, and managed."3 These risks become important to food safety when they have the potential for causing psychological or physical harm, and when they lead to deficiencies in expected food safety behaviors. These risks often stem from work-related stresses caused by the prevailing company culture.4 In other industries, these types of risks have been shown to affect not only the health of the individual employee, but also the "healthiness" of the organization, with the latter playing out as negative effects on efficiency, productivity, product quality, and, ultimately, product safety.

What are some examples of psychosocial risks? If a job flow is organized in an inefficient manner, then the frontline workers may have an extremely difficult time executing tasks, despite their best efforts. If company management is not clear and specific about its corporate goals, then employees could end up working on the wrong things. If the Production Department is continually pushing to get more work done, the frontline workers may quickly feel that they run out of time in a day, no matter how hard they work.

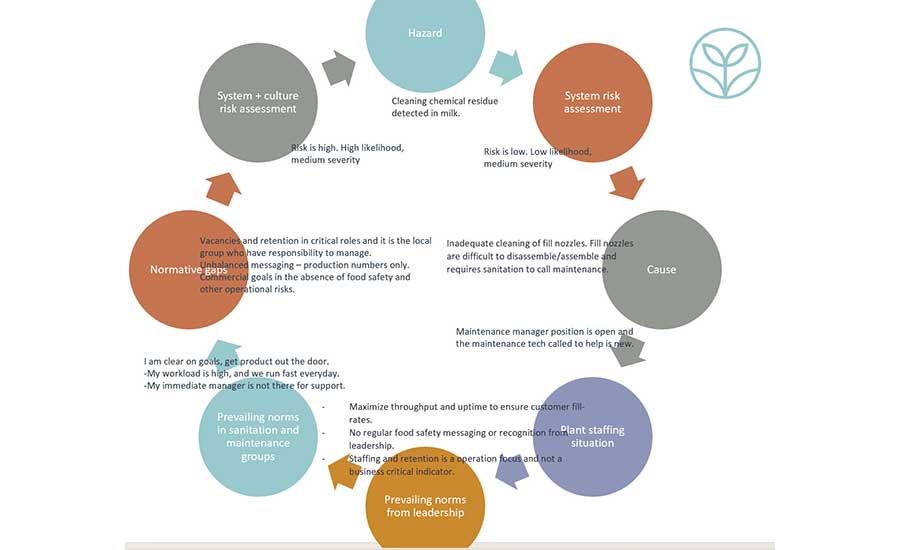

Let us review a real-life example via Figure 3. Note that in the upper right, an identified risk has been assessed as "low" by a classical HACCP analysis. Then, note that as culture and events get in the way, the real risk is "high" (upper left).

The example shows that "organizational chart" issues and company culture ("push") were so impactful on plant food safety behaviors that the company had to deal with an actual retail issue of a contaminant found in its milk.

All of the above examples are meant to indicate that even if all of the biological, chemical, and physical risks are 100 percent controlled (i.e., all critical control points are within specification), psychosocial factors could be so severe and likely to occur that an employee's job behavior is impacted in a very negative manner. Is it not possible that if team members are burned out or overburdened because tasks keep being added to their workload, they may not perform their job satisfactorily and they might do something wrong even though they do not mean to? Maybe the wrong label gets put on a product, causing an allergen risk; maybe the wrong ingredient is put into the recipe; or, much tougher to catch, maybe a cooking temperature is recorded inaccurately.

A company's quality and food safety systems are set up to prevent bacterial contamination of food, to assure that allergens are not inadvertently added to a product, and to ensure that no metal gets into a finished product container. But do these same food safety systems prevent the unseen errors related to cultural impact of psychosocial risks? This is why incorporating psychosocial factors into a HACCP program is so important.

Impact of Culture on Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors exist everywhere, whether or not they are noticed or measured. They can be considered as the expression of control, support, and environment that food company leaders and team members experience as a direct function of their company's culture. Food safety culture can be defined as "the shared values, beliefs, and norms that affect mind-set and behavior toward food safety in, across, and throughout an organization."6

Biases and heuristics are the mental constructs, based on one's experiences, which influence making judgments and decisions. They play a significant role in how people perceive and respond to risks. A person may assume they already know the answer based on past experiences, but what if they are so overburdened at work that they forget what they did last time? Or they frame the problem in an incomplete way and, therefore, make the wrong decision?

A company’s culture and its psychosocial factors influence the making of decisions about food safety risks and can increase or decrease the likelihood of making a wrong decision. This can be especially problematic if the company's culture is immature, or when there is not enough time to get the work done, or if employees are not even sure they are doing the right work.

Company culture is intimately interconnected with food safety risks. Different and competing aspects of organizational culture drive an organization's risk response. If lack of job security and poor job satisfaction are significant negative influencers of a company's culture, might those issues sometimes outweigh everyone's best intentions to follow, review, and adjust the company's HACCP program?

Why are Psychosocial Factors not Built into HACCP Plans?

Around 12–14 years ago, management literature contained many references to psychosocial risks, particularly with regard to employee health and well-being, as well as overall personnel safety in a plant environment. In essence, higher personal stress tended to lead to higher negative health outcomes (which then led to time off work).

At the time, the insights behind psychosocial factors seemed new and useful. Yet, after a short amount of time, interest in psychosocial factors waned considerably, and these factors were never applied to food safety. One major reason for this may be that psychosocial factors are difficult to measure with quantitative metrics to drive behavior changes. In the food industry, we are used to being able to measure bacterial counts, to calculate the quantity of sanitation chemicals so they do not exceed no-rinse levels, and to count the number of bolts used in a piece of machinery so that no unaccounted-for metal falls into a product stream. But how do we measure, for example, "addition sickness"—being asked to take on too big a scope of work or too many different tasks—due to an employee's job not being configured optimally?6

Psychosocial factors may also be difficult to visualize, and therefore difficult to internalize. We can see the cause of bacteria presence, see buckets of chemicals, and see nuts and bolts; but how do we "see" job control and managerial support, for example? We can see what might cause workload overload—a classic symptom of addition sickness—and we might see the consequence of being overburdened, but we are not educated nor trained to see the hazards and risks directly. This is the fourth food safety hazard—"psychosocial"—in addition to biological, chemical, and physical hazards.

Finally, psychosocial factors can be difficult to identify because they appear "new" and subjective. Accepting and addressing such factors can be challenging when a company is used to process and product hazards, not the sociological and psychological hazards.

How Might Psychosocial Factors be Measured?

When psychosocial factors are identified as drivers for a company's food safety risks, the response is almost always one of astonishment and discovery. Leaders quickly realize that these factors can go a long way toward explaining what had been previously unexplainable: that even with the best control points, things still go wrong. Even the best corporate mission statements do not mean that frontline workers feel comfortable enough within their company culture to bring up a food safety issue without fear of consequences.

One method that can be used to encourage companies to better understand the psychosocial factors at play in their organization involves a series of statements adapted from a 2014 study.7 Employees are asked to respond to the following statements:

My workload is satisfactory.

I am usually able to complete my work within normal working hours.

In my department, tasks and responsibilities are clearly distributed.

I am clear about the goals and objectives for my job.

I can influence my workload.

I have sufficient opportunity to plan my own working day.

These statements can help the organization begin to grapple with how psychosocial factors play out in the workplace. As more companies work with these statements, more useful and actionable statements are expected to emerge.

Building a Better HACCP Plan

Companies should start now to build psychosocial factors into their food safety plans and/or into their HACCP plans. Even if there is some lack of consensus on what the factors should be, and even if this type of approach sounds "non-quantifiable" at the moment, start building in something that makes sense to your organization so that everyone becomes involved.

The HACCP hazard analysis should include the psychosocial hazards, just as it already does for the "classical" hazards (biological, etc.). If the organization does not yet believe that psychosocial hazards are on par with classical hazards, then consider treating the psychosocial as a third dimension, layered on top of the biological, chemical, and physical risks. The psychosocial factors can be assessed using the same approach food safety teams already understand: outlining the likelihood and severity of the hazards and assessing which behaviors and cultural practices might turn these hazards into real food safety risks.

Treating psychosocial hazards as just as important as the classical hazards will lead the organization to new realizations for how to improve its food safety culture and practices.

Summary

Psychosocial risks—those aspects of a company's culture related to the job environment—can drive food safety decision-making and subsequent actions. For this reason, it is important to consider psychosocial risks in an overall HACCP analysis. These risks should be made part of the HACCP program, on an equal basis with the classical hazard risks (biological, chemical, and physical). Doing so will lead to improvements in the company's overall culture and its ability to decrease overall food safety risks, while leading to a better environment for its employees.

References

- Frijns, B., F. Hubers, D. Kim, T.-Y. Roh, and Y. Xu. "National culture and corporate risk-taking around the world." Global Finance Journal 52 (2022): 100710. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044028322000126?via%3Dihub.

- Leka, S. and A. Jain. "Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview." World Health Organization. December 2010.

- Derdowski, L.A. and G.E. Mathisen. "Psychosocial factors and safety in high-risk industries: A systematic literature review." Safety Science 157 (2023): 105948. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925753522002879?via%3Dihub.

- Leka, S., A. Jain, M. Widerszal-Bazyl, D. Żołnierczyk-Zreda, and G. Zwetsloot. "Developing a standard for psychosocial risk management: PAS 1010." Safety Science 49, no. 7 (2011): 1047–1057. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925753511000269?via%3Dihub.

- Global Food Safety Initiative. "A Culture of Food Safety: A Position Paper from GFSI." November 2018. https://mygfsi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/GFSI-Food-Safety-Culture-Full.pdf.

- Rao, H. and R.I. Sutton. The Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things Harder. New York, New York: St. Martin’s Press, January 2024.

- Vestly Bergh, L.I., S. Hinna, S. Leka, and A. Jain. "Developing a performance indicator for psychosocial risk in the oil and gas industry." Safety Science 62 (2014): 98–106. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925753513001835?via%3Dihub.

Lone Jespersen, Ph.D., is a published author, speaker, and the Principal and Founder of Cultivate SA, a Swiss-based organization dedicated to eradicating foodborne illness, one culture at a time. Dr. Jespersen has worked with improving food safety through organizational culture improvements for 20 years, since she started at Maple Leaf Foods in 2004. She chaired the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) technical working group A Culture of Food Safety, chaired the International Association of Food Protection (IAFP) professional development group Food Safety Culture, and was the technical author on the BSI PAS320 Practical Guide to Food Safety Culture. Dr. Jespersen holds a Ph.D. in Culture Enabled Food Safety from the University of Guelph in Canada and a master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Syd Dansk University in Denmark. She is a visiting Professor at the University of Central Lancashire in the UK. Dr. Jespersen serves as Chair of the IFPTI board and as Director on the Stop Foodborne Illness board. She is also a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Food Safety Magazine and a member of the Educational Advisory Board of the Food Safety Summit.

Bob Lijana, M.Sc., has held director- and VP-level positions in food safety, quality, and operations for over 35 years at companies producing ready-to-eat foods, prepared meals, and pasteurized juices. He has a B.Sc. and an M.Sc. in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California–Berkeley, respectively.